Implementing a Discovery process at Optimizely

How I reduced cost, increased revenue, and improved product quality by creating an explicit Discovery phase

It was October of 2015, and we just launched Optimizely’s newest product. The one that was supposed to transform us into a multi-product company, diversify our income stream, and rocket us to the next echelon of success.

Instead, the product launched behind schedule, with bugs and feature gaps, and struggled to gain traction in the market. Less than 6 months later, there were company-wide layoffs.

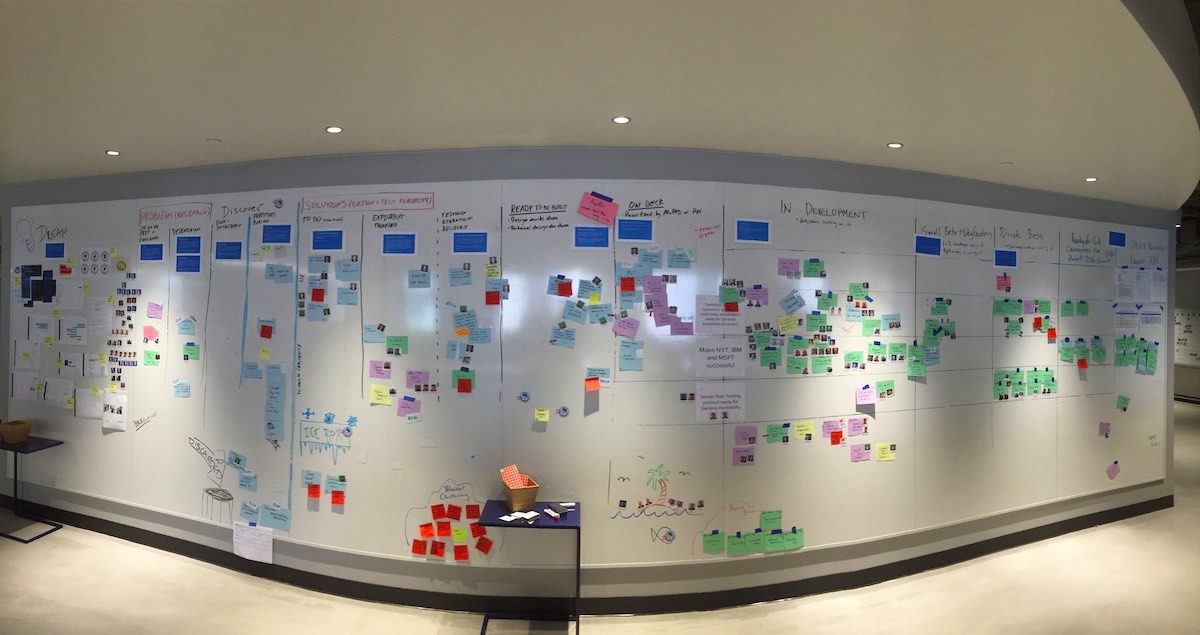

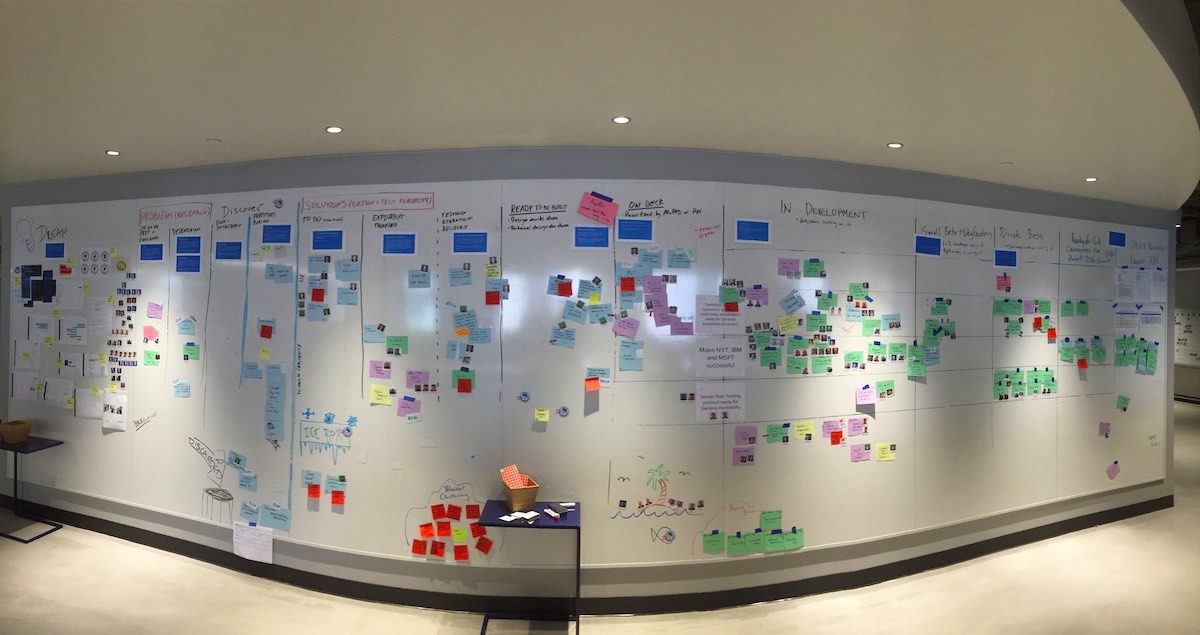

The final discovery kanban board that helped us stay focused on customer needs by tracking work from dreams through delivery

The final discovery kanban board that helped us stay focused on customer needs by tracking work from dreams through delivery

How did we get here?

Optimizely was founded in 2009, and grew to over 400 people by the end of 2014. Design, engineering, and product were around 120 people, split into “squads” who owned a product area and ran their own flavor of scrum.

Design and research was awkwardly shoehorned into each team’s scrum process. Scrum is a process designed to enable engineers to ship code reliably with high quality, not to enable designers to do their best work. As a result, designers were typically assigned to projects in sprint planning when engineers were ready to build. If they were lucky, they’d have a “sprint 0” to do some research to understand the problem they’re supposed to be solving, but often this wasn’t happening. They were given little space to explore solutions, or test them with customers. Their impact was confined to pushing pixels.

Engineers often complained that they were “blocked on design” (a phrase I hate). When they did get designs, there were often open product and design questions, which slowed down implementation, increased bugs, and reduced UI quality.

Product managers had little time to do customer development to inform the team’s vision, strategy, and roadmap. They were too busy managing engineering schedules and performing scrum rituals.

All told, we were shipping features that weren’t rooted in the needs of our customers. We operated as a feature factory.

Let’s build a new product!

We rolled into 2015 building product this way. Now we were asked to build a brand new product from scratch. Oh, and we threw a team of 10 engineers, 3 designers, and 3 PMs on it before doing any product discovery or design work.

We tried our best to do understand the needs of our potential customers and launch a viable product, but we were fighting against the inertia of engineers already writing code. The fact that we got any customers before the end of the year is a minor miracle.

As the manager of the designers and researchers on this project, I had a front row seat to the spectacle. I knew this wasn’t the way to build a product people loved, and that the impact of design and research was severely hampered in this system, but I had been unable to make any headway on changing how we build product since we were so under the gun to launch a new product.

Designing the machine that designs the machines

A wise man once said: Never waste a good crisis.

This was a crisis visible to the whole company. It was clear from the executive team down to the front-line staff that the way we built product wasn’t working. This was my opportunity to design a new operating model that supported researchers and designers doing their best work. A system that…

- Was driven by the needs of customer, rather than solutions looking for a problem.

- Validated what we were building was valuable, usable, and feasible, before we wrote any code.

- Didn’t decide what to build that sprint and then ask, “Do we have designs for this?” but instead had research and design pushing work into sprints.

- Wasn’t overly prescriptive of which UX methods to use, but rather was descriptive of high level phases and suggested methods. It also shouldn’t prescribe who was doing the work. Everyone can and should contribute to the process, regardless of title. What’s important is that the work is being done each step of the way.

- Was understandable to non-designers. The design process shouldn’t be a mystery. If it is, everyone will be questioning what we’re doing and when we’ll be done. Making it understandable to all also elevates the design maturity of the org, while communicating out how far along projects are.

To design this system, I drew on what I learned in grad school, my hands-on knowledge from working as a product designer, my experience managing designers and guiding their work, and my reading about dual track scrum, continuous discovery, and how other teams build product.

After talking through options with the design team and PMs, and trying on some models with projects that went well (and not so well), we aligned on the double diamond model of design.

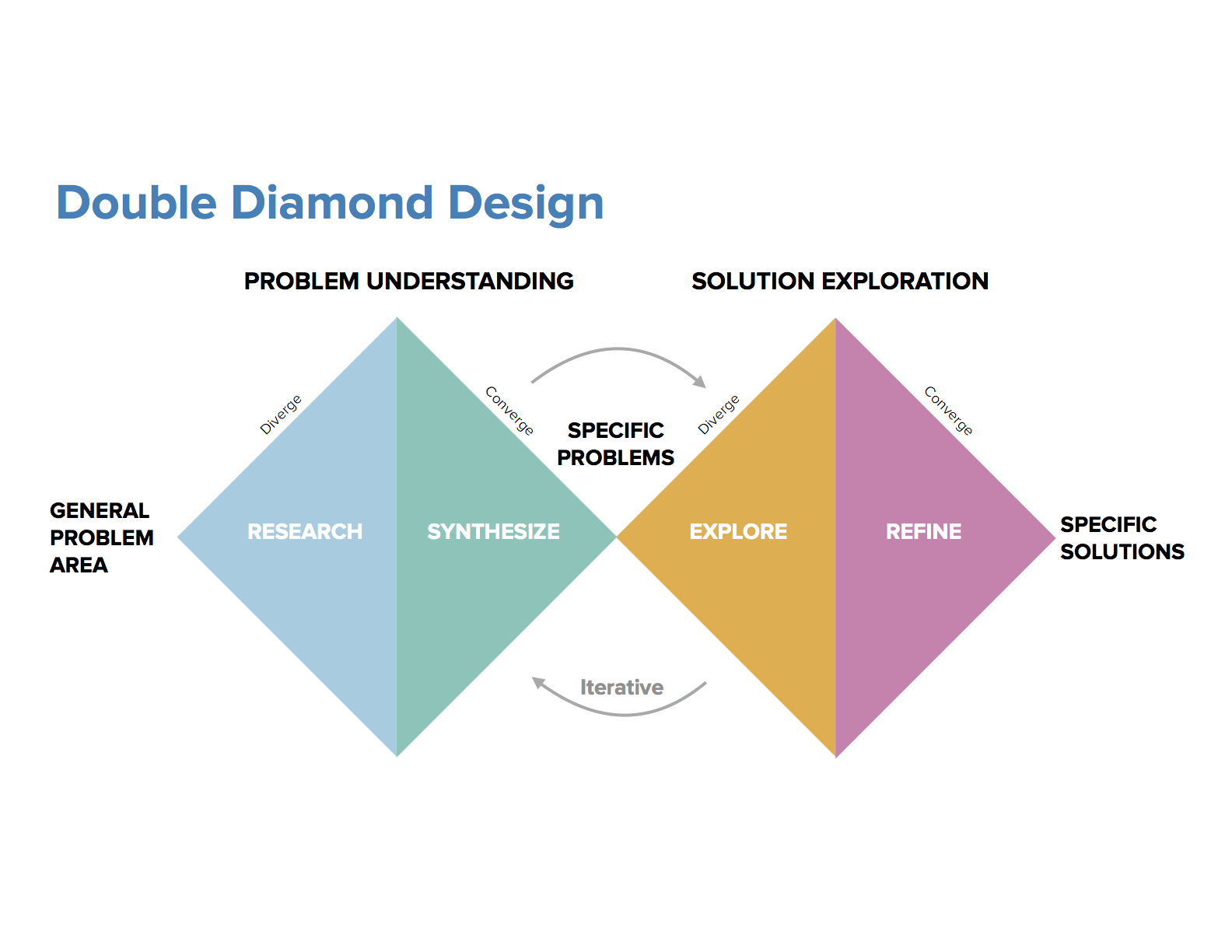

Double Diamond model of design, courtesy the UK Design Council

Double Diamond model of design, courtesy the UK Design Council

This was created by the UK Design Council to model the design process. It’s not overly prescriptive, but has enough structure to both guide the team’s work while communicating what work is being done at each stage.

It splits the process into two phases: problem understanding, and solution exploration. The goal of problem understanding it to define what problem you’re solving, who it’s a problem for, and use cases that are in and out of scope.

Solution exploration’s goal is to find the best solution to the problem by exploring potential options, testing them with customers, and vetting their technical feasibility.

Each phase is a diamond because it has two halves, which represent divergent and convergent thinking. Divergent means going broad to gather lots of information and ideas, whereas convergent means whittling those down to the most promising ones. These two modes of thinking personally helped me become a better designer by telling me when I should turn on the generative part of my brain, and when I should turn on the evaluative part of my brain.

Once the work has gone through this process, it’s ready to be built and can be prioritized in a sprint. By this point we should have high confidence that the solutions are valuable, usable, and feasible. I called the system Discovery Kanban.

Roll out

Now that we had a new proposal for how to work, I started using it with one team who’s designer and PM were ready to try a new way of working and smoothing out the kinks. We made the kanban board on a whiteboard, put their current and upcoming work on it, and started reviewing it in sprint planning.

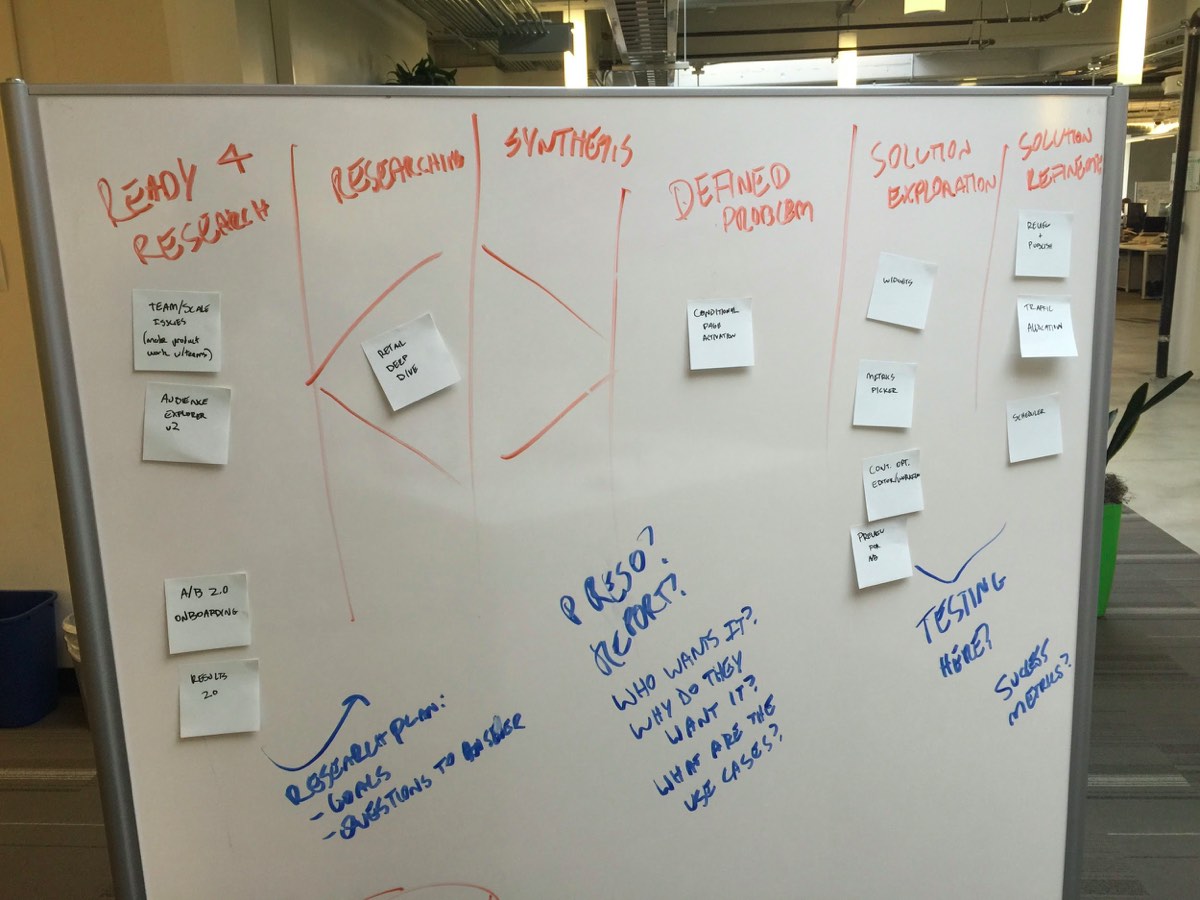

First prototype of the Discovery kanban board

First prototype of the Discovery kanban board

There were a couple of quick improvements to make, such as adding a column for problem definitions that were done but not being worked on by a designer yet, but otherwise the system was accurately modeling reality and increasing the visibility of the team’s work.

After a few weeks, the early results were positive. We were explicit about which projects needed more research, and which didn’t. Designers had more space to explore potential solutions. Finished designs were flowing smoothly into engineering. Their estimates were more accurate, there were fewer questions during the implementation phase to slow them down, fewer bugs at launch, and more room for UI polish.

Expanding to more teams

Once it was working for one team, I expanded team by team until all the squads were using this system. Doing it this way helped me get buy-in for this new way of working, explain the design process, and address any confusion.

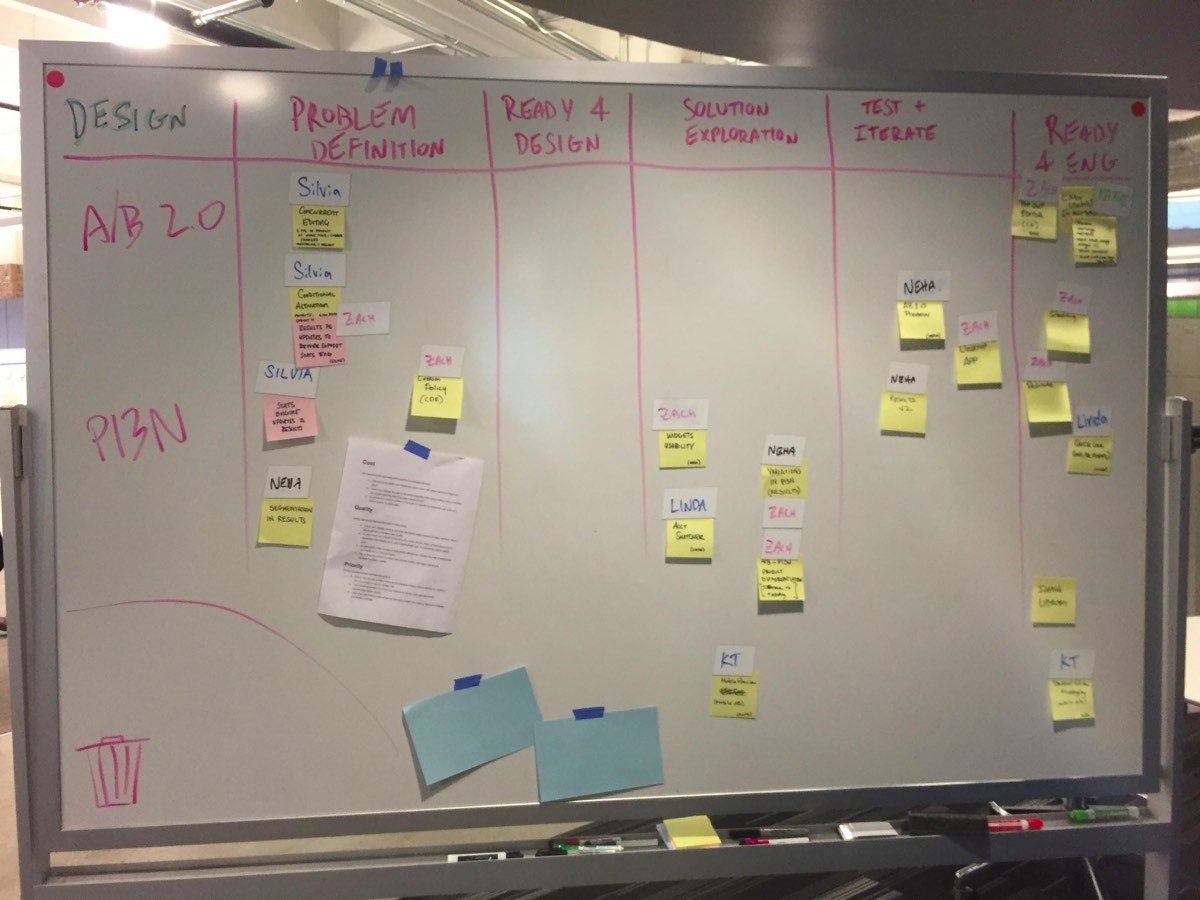

Next iteration of the Discovery kanban board

Next iteration of the Discovery kanban board

I also started a weekly planning meeting with the designers, researchers, and PMs to review all the work in flight, and prioritize new work. This ensured we were working on the most impactful projects that were aligned to our product strategy and vision, helped us choose which projects were most in need of research across teams, improved coordination between teams, and reduced the number of meetings of “work about the work” (i.e. who is doing what, and when). Put simply, it aligned design’s efforts to business outcomes.

While I was doing this, our Engineering Development Director was improving how we tracked and coordinated engineering work across teams. I stayed in sync with him, and we moved all the work onto a huge physical wall that tracked everything the product, design, and eng teams were working on, from vague ideas through discovery to shipped code.

Discovery kanban board in its final, full board form, tracking work from dreams through delivery

Discovery kanban board in its final, full board form, tracking work from dreams through delivery

We also expanded my weekly planning meeting to include engineering and product leadership, and to review all work in flight, from what engineers were building back to the exploratory research. This greatly increased visibility into what everyone was doing, what customer pain points and opportunities most needed research, and what cross-team prioritization and trade-offs we needed to make.

Meeting to review the whole board, expanded to include engineering and product leadership

Meeting to review the whole board, expanded to include engineering and product leadership

Impact

All of these changes are great, but what was the impact of this new system on the company? I’m glad you asked:

- Doubled velocity: We were shipping twice as many roadmap items (features, UI improvements, and so on) as the year-ago quarter, across all squads, while keeping headcount flat. We were finishing twice as many research and design projects, with a smaller team. The system provided better coordination across teams (no more 2 designers working on the same project, for example), and reduced the number of meetings need to talk about “work about the work,” i.e. deciding who was doing what, and when they were doing it.

- Improved quality: There were fewer bugs with new feature launches, there were fewer code yellows and reds, and we were doing more UI polish for features. This is largely attributable to engineering not starting to code until the designs were ready and fully thought through. This meant work flowed smoothly through the system, estimates were more accurate, and people weren’t rushing to ship.

- Higher morale: Designers and researchers were happier and felt like the process supported them doing their best work. Engineers weren’t stretched as thin, have stopped saying they’re “blocked on design.” They’re also involved in discovery work which helps them understand the “why” behind their work better. PMs also had more space to do customer development.

Those are all great measure of the output, but what about impact to the bottom line and your customers?

- Increased revenue: Remember that failed product we launched? Well we kept iterating on it, and grew it to over $2MM in annual recurring revenue within the first year. Our process made sure the team was staying close to customers, and understanding their needs first, before jumping into solutions and code.

- Increased Cost Savings: A back-of-the-napkin cost calculation puts the cost to build our new product at a conservative $6.25MM (~250K per person per year fully loaded, * 15 people, * 10/12 years). (That doesn’t include additional engineers we added later, or the cost of training sales and support, or the cost of launch marketing. Nor does it include opportunity cost of launching late, and not gaining customers at launch). Under this new system, we would have started with a smaller team (a researcher, designer, and PM, let’s say), figured out the customer need to serve first, and tested solutions until we were confident in the value of investing more time and people into launching a product.

Reduced churn: We spent most of 2016 iterating on the new product, and starved our original product of resources. As a result, customers were fed up with longstanding bugs and feature requests that weren’t being acted on, and churn was a serious problem.

To solve our churn problem, our CFO/COO led an effort to build a current reality tree to identify all the issues — product-related or otherwise — that contributed to churn. Getting them all out in the open helped us prioritize them and assign owners. In that exercise, 210 product issues were identified (a lot more non-product ones were identified, too, like poor handoff between sales and success). These ranged from missing features to bugs to UX problems.

Throughout the rest of 2017 we took them on, and were able to cross 152 items off the list — while shipping additional new features. By the end of that year, churn finally started decreasing. This was a testament to the strength of our system that it didn’t buckle under the weight of all these problems to solve, and ensured we took the time to understand our customer’s pain points, and tackle the most impactful ones, instead of rushing into building half-baked solution.

Fin

The way we worked in 2015 wasn’t working. By the end of 2016, we had transformed the way we built product, resulting in increased velocity, increased quality, increased revenue and decreased cost. And in 2017 these new habits became our default way of working. We started with the needs of customers, and then figured out how to solve them, rather than the other way around. Whenever I would hear the CEO ask, “Do we understand the problem well enough yet, or do we need more research?” I knew I had achieved the shift in mindset we needed. Seeing the design team’s work flourish under this new system was a highlight of my career.

Want to transform the way your team works? Get in touch at jlzych@gmail.com